Local Indigenous History

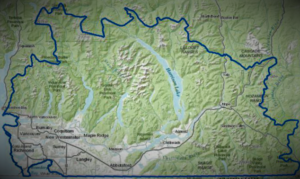

First Nations people have lived in the Fraser Valley for many thousands of years. Migrations of Indigenous peoples through this area over centuries are remembered in oral histories. This is also observable in the archaeological record, as well as through linguistic analysis. Stó:lō, or the “people of the river” in Halq’eméylem, refers to a band of tribes spread out from the Pacific along the banks of the Fraser River.

The word Coqualeetza is said to mean “beating blankets,” and there are a few variations of the story of how the location got this name. Some versions simply relate the habits of Stó:lō women washing their laundry in the nearby Luckakuck creek.* Others weave a tale of a fishing expedition of men from a nearby village long ago: these husbands decided to stay at their fishing camp for several days rather than share their catch with their hungry wives back at home. The wives got word of this from a young boy who snuck away from the camp to bring food to his mother. The women angrily beat the blankets of the men (an unlucky practice) as they hurried down to the men by the river. Depending on the version, several creatures such as the raven, beaver, and sockeye salmon are said to have been created of this event, transformed from unfortunate husbands cursed by their furious wives.

The Stó:lō’s first encounters with European colonization were indirect. A smallpox epidemic had decimated the region decades before white explorers arrived in the early nineteenth-century. The area may have already been visited by waves of viral and bacterial diseases imported from Europe for generations. These pandemics travelled along continent-wide trade routes that had existed for millennia. The fur trade network had already become an important feature of intercultural exchange by the early 1800s. Face-to-face contact officially began in 1808 with Simon Fraser’s exploration of the river which today bears his name.

European settlement accelerated quickly after mid-century as exploration and the goldrush brought enterprising prospectors, pioneers and missionaries over the decades that followed. It also brought alcohol and an increasing disruption of Indigenous traditions. Interactions between the Stó:lō and the white settlers were not always negative, many natives acted hospitably toward starving outsiders, and Christian missionaries did their best to buffer some of the cultural damage brought by European society. However, the condescending Victorian attitudes of the Church and various levels of government towards First Nations people resulted in social tragedies that are still felt today, largely caused by the residential school system.

Coqualeetza was chosen as the place to build a residential school in 1889, three years after a local minister had begun offering education in his home to local Stó:lō children. The Methodist Church (later merged into the United Church of Canada) was responsible for the education and well-being of the students. Coqualeetza has the undistinguished status of few to no instances of sexual abuse and is known to have had an almost pleasant atmosphere. This is compared with the sadly low bar of other, largely Catholic, residential schools in the region. Some students from the home were even accepted into local secondary schools. This is all weak rationalization, however. The pupils were taught little in the way of scholarly instruction, mainly learning to farm and keep house. Children were still stolen from their families, consistently beaten and scolded into learning Anglo-Celtic ways; damaging the families and communities of Stó:lō people for generations.

In 1941, when the school was designated to become a tuberculosis hospital, the students were suddenly transferred to the notorious Alberni Residential School on Vancouver Island. Some children were already hundreds of miles from home, some would never return. Upon its opening, the tuberculosis hospital was described as experimental in concept and could serve as a model for mainstream hospitals. Unsettlingly, one elder has claimed that the doctors were actually testing unproven tuberculosis treatments on Indigenous people there, although this is unsubstantiated. Clearly, not much good had come from this site while it was in the hands of either the Church or the federal government.

*Luckakuck was the affectionate name given to a hazardously slippery log which was used as a crossing for the creek, causing people to straddle it when they fell.